|

TIME

August 21, 2000

Bound to Wander

In Indonesia's second city, the itinerant Madurese have found a place they can call home

By ANTHONY SPAETH

| |

John Stanmeyer / Saba for TIME

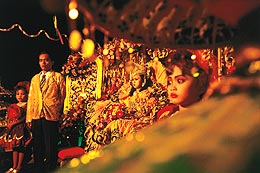

MADURESE MARRIAGE:

The Madurese adhere to their distinct

culture,

as in this colorful marriage rite.

|

If you stand at the harbor of Surabaya, Indonesia's famed port and second-largest

city, you can see the island of Madura only 4 km across the water. For

a decade, there was a plan to connect the city and the island with a

bridge, but financing never came through and the only progress was a

few premature concrete pillars that now stand forlornly in the sea.

A bridge would certainly be useful: every day, thousands of people from

Madura cross by ferry to Surabaya, jammed in with livestock, cargo,

cars and buses. The ferries run 24 hours a day. "I've been making this

trip every day for 13 years," says Hasmat Nabiri, 64, a Madurese day-laborer.

The reason for the exodus is simple. "We come to work," says Nabiri.

Madura is home to a unique language and culture that sets its natives

apart from the people of Indonesia's other islands. And yet it is barely

home to its own people. Of an estimated 10 million Madurese, 6 million

have relocated permanently to places that offer more work. Others, like

Nabiri, spend a good part of their lives on ferries back and forth to

Surabaya. This makes the Madurese the most itinerant of all Indonesian

ethnicities, a people banished from their home by economic circumstance.

To a lesser extent, and for varying reasons, other Indonesian groups

share that destiny. For decades, the central government in Jakarta has

promoted large-scale "transmigration" to alleviate overcrowding. Java

is the country's most densely populated island, so its people have been

officially moved across the map: to Sumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan and

Irian Jaya. There were social engineering ambitions within the plan.

Javanese culture was expected to take over, especially in troublesome

spots like East Timor. In its defense, the concept could also have forged

a common identity among Indonesia's varied peoples.

It hasn't worked that way. In West Kalimantan, brutal warfare between

the local Dayaks and immigrant Madurese has flared intermittently for

the past three years, claiming thousands of lives. East Timor has left

the Indonesian fold entirely. The biggest challenge facing Indonesia

is to quell various ethnic conflicts and hold together as a nation.

Surabaya contains the mix of people one would expect in a bustling port

town: Javanese bureaucrats, Chinese traders, even a small Arab community

descended from seafaring merchants. When the eye adjusts, one notices

the Madurese and their place on the lowest rung of Surabaya's employment

ladder. They number about 800,000—a fourth of the city's population.

They peddle cigarettes, pimp for brothels, collect scrap metal and,

with their fearsome celurits—a kind of machete—help the city's

underworld run smoothly. "Madurese work the jobs the Javanese don't

want," says Hamad Mataji, one of the most prosperous figures in the

Madurese community.

Mataji arrived here penniless 25 years ago. He dug trenches, pulled

a pedicab and retreaded tires to make money. When he had enough, he

bought a 3,000 sq m lot that has become the city's central exchange

for scrap metal. Now 50, Mataji carries a mobile phone, and his smile

reveals a mouthful of teeth made from white gold. But he still works

the yard every day, signing receipts from scrap-hauling scavengers—a

great many of them fellow Madurese—and getting a different kind

of visit from local politicians and cops. "Everyone these days is asking

for a loan," he laughs.

Many things have changed in 25 years, Mataji says. The Madurese have

been driven out of the local gambling and prostitution businesses. (Those

trades are now backed by Chinese-Indonesians and the Indonesian military

and police.) But their reputation as proud and rough characters hasn't

diminished. "The Madurese would rather steal than beg," says Mataji.

Sapan, 42, used to run with a Madurese gang in the Surabaya underworld

until the early '80s, when thousands of suspected criminals were mysteriously

murdered. Sapan says he has killed 20 men, mostly in disputes over women.

"We are fearless," he says. "We die when we are meant to die." Sapan

found religion after too many years in jail, he says, and has returned

home to Madura to work as a farmer. But his story fits the Madurese

stereotype: a people brave and clannish, with their own code of honor

(known as carok)—and a propensity for violence. "Treat them well

and they'll be even nicer," says Fachrul Rozi, a Madurese doctor. "But

if you're mean to them, they'll be even meaner." Dede Oetomo, an anthropologist

at Surabaya's Airlangga University, observes, "With the Madurese, it

is a very thin line between gangsterism and normality." That's not all

bad. Most of the city's security guards are Madurese, and they're known

for protecting premises with fierce loyalty. Says Nazirman, who has

Madurese guards at his office supply store, "What they bring is their

courage and a will to work."

In the center of the city is Surabaya's largest red-light district,

Dolly, named after a pioneering madam from the 1960s. Ronny, a native

Madurese, has worked for the Wisma Jaya Indah brothel for 25 years.

It's the only job he has ever had. Ronny used to go to the countryside

on recruiting missions for the brothel, but these days he spends his

days on the pavement outside. "I mainly do security and try to bring

guys in." The night is slow, and a group of visiting Koreans are reluctant.

"Only 50,000 rupiah [$6] an hour," Ronny promises them. One of the Koreans

takes the bait, the others move on.

In the industrial port of Gresik on the outskirts of Surabaya, Madurese

work together to get by. The remains of a decommissioned Indonesian

warship are sunk in shallow, oily waters close to the shore. For six

months, a group of 20 Madurese have been carving it up for scrap. Covered

in oil and up to their waists in sludge, the men use propane torches

and heavy saws to disembowel the vessel. "There won't be anything left

of this ship when we're done with it," foreman Syaiful Bakri says proudly.

The pieces will then find their way around the country, thanks to the

extensive network of Madurese traders. That's good for the scavengers:

the process cuts out the middlemen who usually skim off so much profit

in the Indonesian economy.

The Madurese network helps newcomers find jobs in Surabaya, too, whether

it's selling fruit or cigarettes on the street or collecting discarded

plastic bottles and bald tires. The community is centered in the northern

part of the city, where Madurese live together in tiny, makeshift houses.

"They believe in coexistence, not assimilation," says Daniel Sparingga,

a sociologist at Airlangga University. Such aloofness can cause problems:

in tough economic times such as these, Madurese are often blamed for

increasing car thefts, pickpocketing and other petty crimes. That leads

some to predict real friction if the economy continues to stagnate,

not a happy thought considering the Madurese and their fearsome celurits.

"We're not afraid to use them if we have to," says Sapan, the former

convict. So far, though, the mix has worked. However humble, the Madurese

have their place in Surabaya, where the ethnic balance remains far healthier

than in many other troubled Indonesian cities—a land of millions

of people living far from their homes.

Reported by Jason Tedjasukmana/Surabaya

atas

|